Passato Prossimo with Essere (to be)

| Listen to the audio file and write the correct number associated with these famous people. Then click here for the answers.

|

You have probably noticed that some past participles presented a different ending vowel than the usual –o. That happens when it is preceded by a form of the auxiliary essere (sono, sei, è, etc) and not avere (ho, hai, ha, etc.) and refers to a subject (the person or thing doing the action or being described) other than masculine and singular.

| (lei: sing. feminine) |

è |

nata |

She was born |

| (lei: sing. feminine) |

è |

andata |

She went |

| (lei: sing. feminine) |

è |

arrivata |

She arrived |

| (lei: sing. feminine) |

è |

diventata |

She became |

| (loro: pl. masculine) |

sono |

nati |

They were born |

On the contrary, the Past Participle keeps the –o if the subject is masculine and singular, as it always does (regardless of the number and gender of the subject) when the Passato Prossimo is formed with avere.

| (lui: sing. masculine) |

è |

stato |

He has been |

| (lui: sing. masculine) |

è |

cresciuto |

He grew up |

In fact, the Past participle preceded by essere, works as an adjective and must agree in number and gender with the subject of the verb. If the subject is masculine and singular the past participle ends in -o (nato, andato, etc.), feminine and singular in -a (nata, andata, etc.), masculine and plural in -i (nati, andati, etc.), and feminine and plural in -e (nate, andate, etc.).

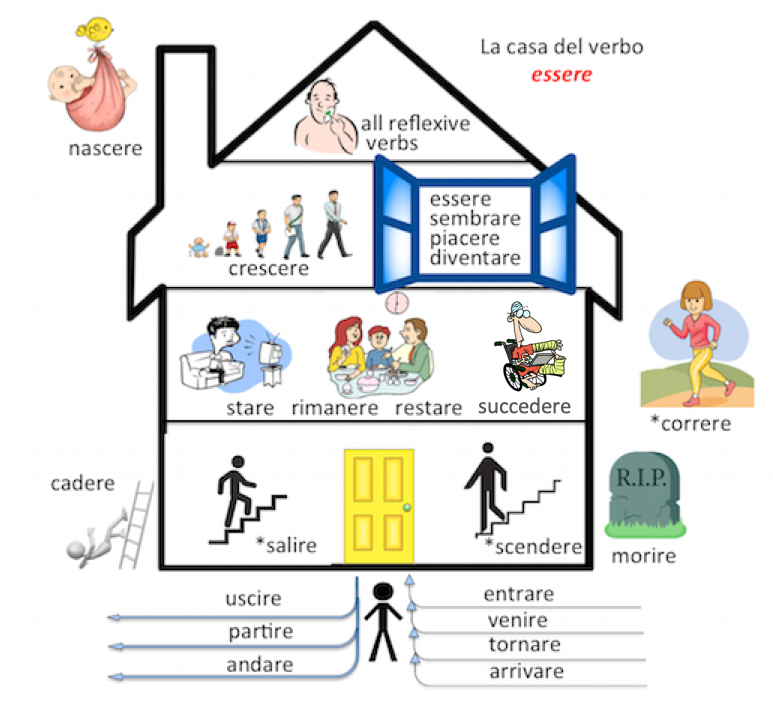

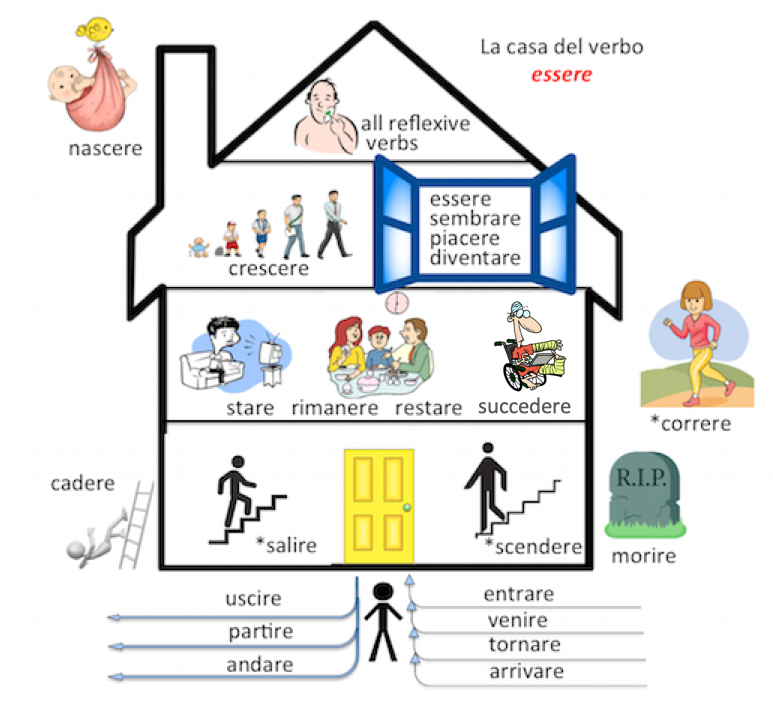

Which verbs require essere as the auxiliary verb? See the verbs that are located in La Casa del Verbo Essere and read the Grammar section below.

| GRAMMAR

How to form Passato Prossimo with essere (to be)

As you have learned in the previous chapter, the majority of Italian verbs use avere as auxiliary. Other verbs (not many) use essere. A very important thing to keep in mind is that the Past Participle of the verbs conjugated with essere (unlike the verb avere) must agree in gender and number with the subject (the person, animal doing the action, or being described). See the difference between the two constructions:

| Passato prossimo with Avere |

Passato prossimo with Essere |

Pino ha mangiato una mela

Alessia ha mangiato una mela

Pino e Mario hanno mangiato una mela

Alessia e Anna hanno mangiato una mela |

Pino è andato in vacanza

Alessia è andata in vacanza

Pino e Mario sono andati in vacanza

Alessia e Anna sono andate in vacanza |

So, every time you want to talk about something that happened in the past (this morning as well as ten years ago) with the auxiliary essere, you must combine the present tense of essere and the Past Participle of the verb you want to make past, according to the gender and number (singular/plural) of the subject. Of course, the subject pronouns (io, tu, noi, voi and loro) can be masculine or feminine according to the person(s) they refer too: Io (man) sono cresciuto in Italia / Io (woman) sono cresciuta in Italia (I grow up in Italy), etc.

Essere

(Present tense) |

+Past participle |

= Passato Prossimo |

(io) sono

(tu) sei

(lui/lei/Lei) è

————

(noi) siamo

(voi) siete

(loro) sono |

stato/a

andato/a and so on

———-

stati/e

andati/e and so on |

Pino è stato /andato etc. (m. sing)

Alessia è stata /andata etc. (f. sing.)

——————————————————

Pino e Mario sono stati / andati etc. (m. pl.)

Alessia e Anna sono state / andate etc. (f. pl.) |

- The previously studied (see Unità 4.1) c’è (there is) and ci sono (there are) follow the same pattern when expressed in the Passato Prossimo. C’è becomes c’è stato/a and ci sono becomes ci sono stati/e depending on the subject: Ieri c’è stato un concerto interessante (Yesterday there was /has been an interesting concert), Ieri c’è stata una conferenza interessante (Yesterday there was /has been an interesting conference), Ci sono stati alcuni incidenti (There were /have been some incidents), Ci sono state alcune proteste (There were /have been some protests)

- To make a negative Passato Prossimo, you simply had non in front of it: Giovanna è cresciuta in Italia > Giovanna non è cresciuta in Italia (Giovanna didn’t grew up in Italy)

- The auxiliary essere always precedes directly the past participle. The only words that can come between the auxiliary and the past participle are adverbs like sempre (always), mai (never), ancora (yet), già (already): Non sono mai stato in Italia (I have never been to Italy)

When to use the auxiliary essere

There are no unequivocal rules for choosing essere instead of avere, but rather some practical clues.

- The auxiliary essere is used to form the past tense of itself: Sono stato bravo I have been good, Siamo stati in Italia l’anno scorso We have been in Italy last year)

- The auxiliary essere is used to form the past tense of most intransitive verbs, especially those involving movement (andare ‘to go’, partire ‘to leave’), inactivity (stare ‘to stay‘, rimanere ‘to remain‘), transformation in the state of being (crescere ‘to grow‘, morire ‘to die‘, cambiare ‘to change‘), appearance (sembrare ‘to seem‘ ‘to look like‘) and events (succedere ‘to happen’ ). Note the past participle of essere and stare are equivalent in Italian: I have been and I have stayed are both translated as Io sono stato/a

- The auxiliary essere is also used with all reflexive verbs and the verb piacere (Unità 14.2)

While it is a good idea to keep it in mind, it may also be helpful to memorize the most common verbs that go with essere using La casa del verbo essere

Note: a) succedere (to happen) has an irregular Past participle (successo); b) the verbs indicated with an* (correre, salire, scendere) can also form with avere (see Unità 14.3). |

Tasks

- Look at the above pictures. Try to imagine what Leonardo Di Caprio, Cobe Bryant, etc. did yesterday. Using the verbs in La casa dell’essere, write one sentence for each character. Then, use Spell and Grammar Checker to check if there are mistakes in your written Italian.

- Work with another student. Ask he/she e… (you both can check your spoken Italian using Speech to Text):

- When and where was he/she born?

- When did he/she arrive to New York?

- Where did he/she did go to High School?

|

Practice

Previous > U13 Reading passages, songs, video clips, etc.

Next > Mi è piaciuta la tua festa. Mi sono divertito